[This article was originally written in Spanish and translated into English with the help of ChatGPT]

As part of my role as CEO, I believe it’s important to occasionally take a deep dive into the workings of a key business process—whether it’s how we close deals, a security procedure, or perhaps the details behind how we account for expenses from a major supplier.

During these reviews, I often ask my colleagues why a process works the way it does: Why do we account for a rebate at this point and not at another? Why is it the consultant, and not the key account manager, who’s responsible for the final version of a document? That sort of thing.

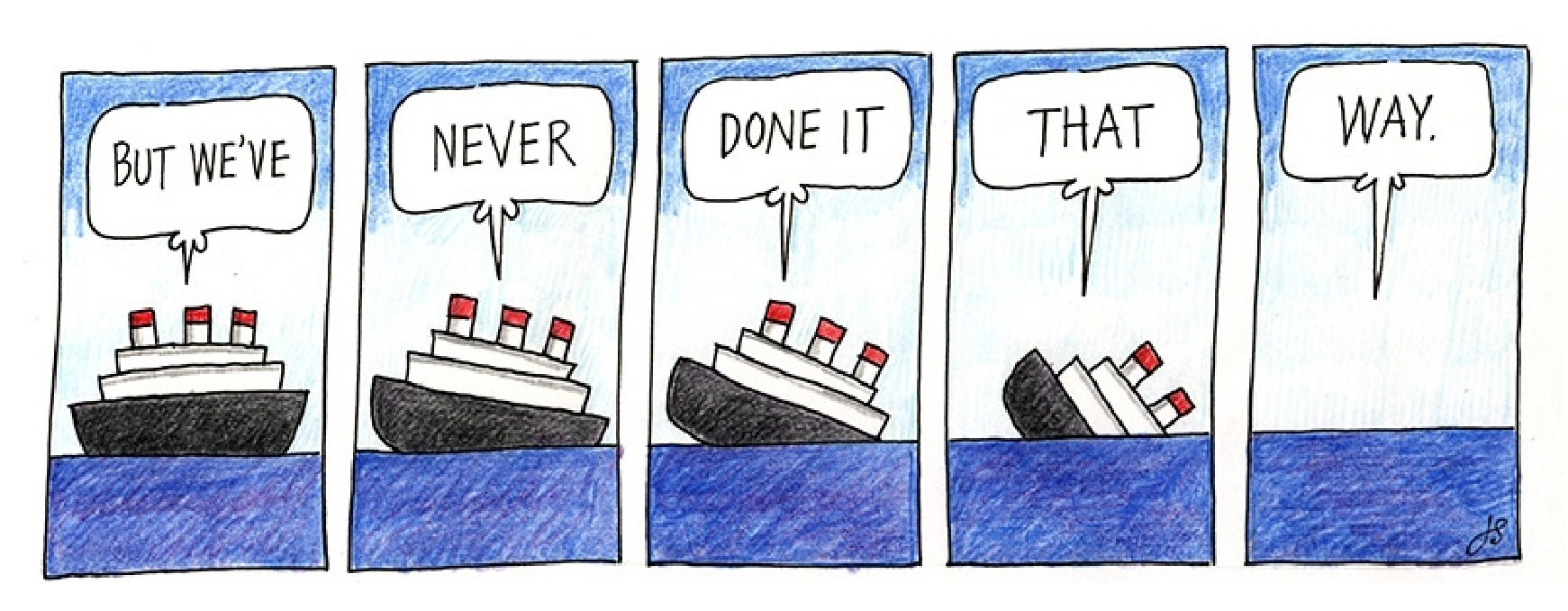

And, more often than I’d like, I get the same answer: “I don’t know, it’s always been done that way.”

Sigh…

Why do we get this kind of response? We all know that inertia is rarely a good justification for anything. So, why does it happen?

A cynical answer would be: “Because people don’t care,” “Because people aren’t interested,” “Because people don’t have what it takes.” I won’t pretend that’s never true—but in my experience, the people we work with do care, and they do want to do a good job.

So why would someone who genuinely cares about their work respond with “I don’t know, that’s just how it’s always been,” instead of proactively trying to improve the process?

Learned Helplessness

“Learned helplessness” happens when someone believes they can’t escape a negative situation—so they stop trying. For instance, a student who constantly fails might end up thinking that no matter what she does, she’ll never pass, and eventually give up trying altogether.

Learned helplessness is a concept that can have serious consequences—like depression. But even without going that far, I think it explains certain behaviors we see in companies all the time.

The idea for learned helplessness came from animal experiments. Two dogs were given small electric shocks at the same time. One of them learned that pressing a lever stopped the shock; the other had a lever too, but pressing it did nothing. The shock only stopped when the first dog pressed its lever. So, the second dog learned that the shocks were random and unavoidable.

Then, both dogs were placed in separate boxes with two sides, separated by a low barrier they could easily jump over. When a shock was applied to their side of the box, the first dog—who had learned that its actions could stop the pain—quickly figured out it could escape just by jumping to the other side.

The second dog, though, who had learned that nothing it did mattered, didn’t even try to escape. It just stayed put, enduring the shock until it stopped on its own.

Learned Helplessness at Work

In companies, we often create situations that encourage people to throw in the towel and stop trying to change the status quo:

Software tools that don’t work properly, and that users have no power to fix or improve.

Needlessly long or complex processes that never get prioritized for improvement.

Poorly maintained facilities.

Suggestions that routinely get ignored or dismissed.

Etc.

These things go beyond each individual case. When several of these frustrations build up, we start to internalize the idea that “nothing’s ever going to change,” and we stop trying to make things better.

How to Turn It Around

In any company there are hundreds—or thousands—of tasks, problems to fix, and projects fighting for attention. We can’t do everything at once, and certainly not in a cost-effective way.

But even acknowledging those limits, it’s the responsibility of company leaders—from team leads to the CEO—to push back against a culture of learned helplessness.

Or, to put it positively: our mission is to foster a culture where everyone in the organization feels they have the power to change things.

Like any cultural change, this takes time—months or even years. And it’s hard. You can’t fix it by sending two emails and hanging up four posters. Cultural change comes from consistent, repeated communication—and most importantly, from leading by example, starting with the CEO, continuing through the executive team, and filtering through the entire organization.

What Can We Do?

Empower teams: Give people the training, autonomy, time, and budget to improve their own tools and processes—without relying on some third party’s “random prioritization.”

Tackle the chronic annoyances: Prioritize fixing those persistent little things that have been around for so long they’ve just become part of the scenery.

Encourage critical thinking: Use follow-up meetings, one-on-ones, and other moments to drive the message that we should always be questioning why things are done the way they are.

Lead by example: Show a genuine interest in how processes work. Listen actively to explanations and frustrations. Publicly support improvement initiatives—even small ones. And be the first to challenge the status quo in a constructive way.

Eventually, that dreaded phrase—“I don’t know, that’s how it’s always been”—will fade away.