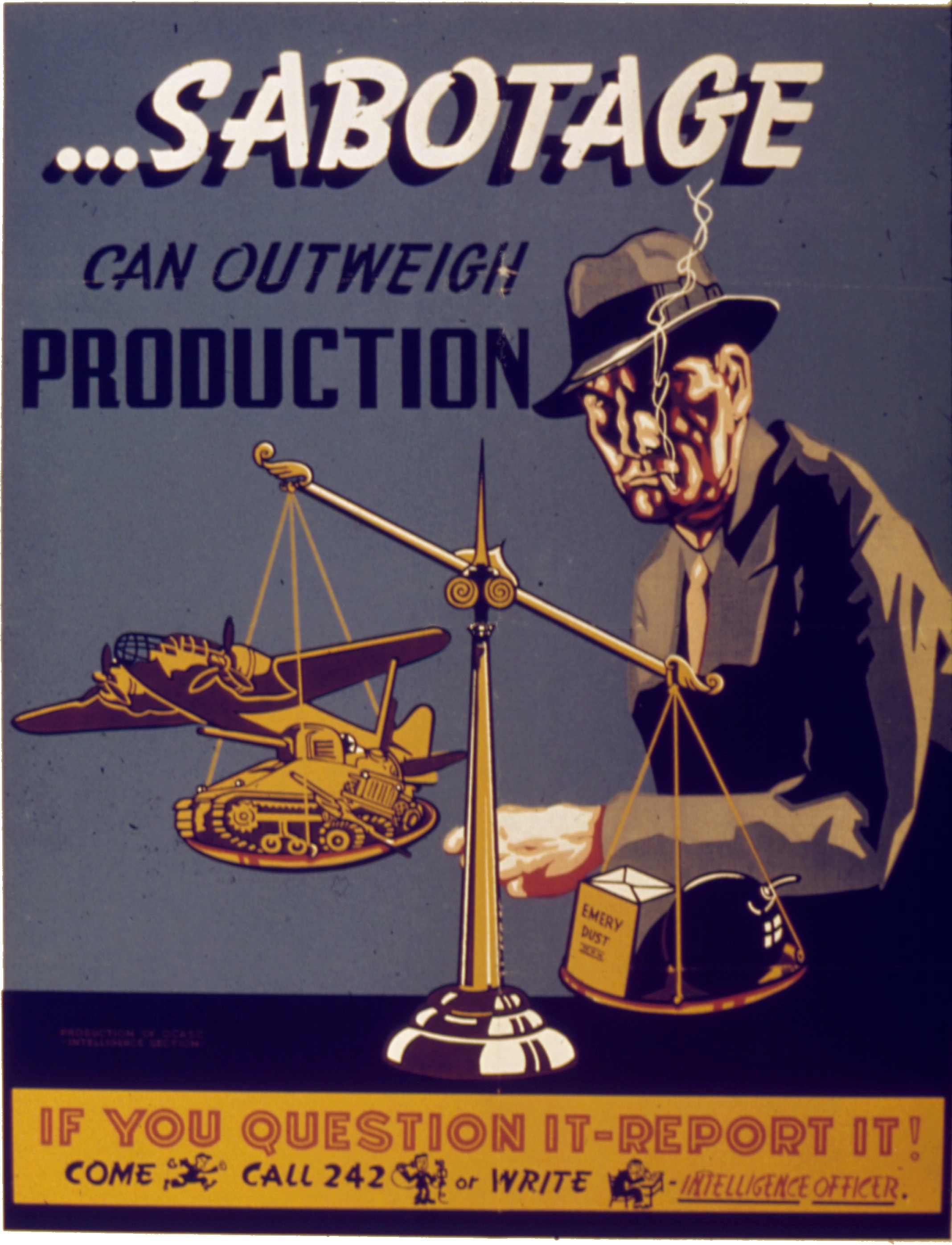

You are probably aware that in 1944, during the II World War, the CIA (or, rather, CIA’s precursor, the OSS - by the way, if you are into spy movies, there is a movie about the OSS and the beginnings of the CIA, The Good Shepherd) wrote a manual called Simple Sabotage Field Manual.

I’ve been meaning to read it for a long time and I finally got around to it while on vacation in my mom’s village this summer. It’s actually not that long, just 40 pages, and quite an easy read.

As managers and leaders, we’re often looking for advice in all the usual places — MIT Sloan Management Review, Harvard Business Review, leadership books, or even maybe TED Talks. But the “Simple Sabotage Field Manual” gives us some real insights—just, of course, not in the way it was intended.

This manual was written to teach ordinary citizens to subtly disrupt businesses and governments by using everyday methods … which are familiar … It’s full of tips like creating inefficiency, increasing bureaucracy, and promoting confusion. It’s like reading a “how not to work” guide.

But if you flip the sabotage advice on its head, you get quite a few leadership lessons.

Here’s what I think we as CEOs can learn from a WWII sabotage playbook.

1. You really really need to foster collaboration

One of the first tricks of sabotage? Stir up discord. This is immediately stressed at the very beginning, in page 1!

“A second type of simple sabotage [...] is based on universal opportunities to make faulty decisions, to adopt a non-cooperative attitude, and to induce others to follow suit. [...] A non-cooperative attitude may involve nothing more than creating an unpleasant situation among one's fellow workers, engaging in bickerings, or displaying surliness and stupidity.”

“Never pass on your skill and experience to a new or less skillful worker.”

The flip side of this is clear: **foster collaboration, and solve problems quickly.**

Creating an environment where your team collaborates smoothly isn’t just about everyone getting along; it’s about helping each other to get the job done. Deal with conflicts early, or better yet, prevent them from starting at all. At Dékuple, we have “Campaign Retrospectives” to talk through what worked and what didn’t. No finger-pointing—just improvement.

Because when you cut out the bickering, you make space for progress.

2. Bureaucracy: The Saboteur’s Best Friend

Saboteurs love bureaucracy. It’s their number one tool for slowing things down.

“Insist on doing everything through "channels." Never permit short-cuts to be taken in order to expedite decisions.”

“When possible, refer all matters to committees, for "further study and consideration." Attempt to make the committees as large as possible - never less than five.”

“Haggle over precise wordings of communications, minutes, resolutions.”

“Be worried about the propriety of any decision - raise the question of whether such action as is contemplated lies within the jurisdiction of the group or whether it might conflict with the policy of some higher echelon.”

“Demand written orders.”

“Multiply paper work in plausible ways. Start duplicate files.”

“Multiply the procedures and clearances involved in issuing instructions, pay checks, and so on. See that three people have to approve everything where one would do.”

“Apply all regulations to the last letter.”

Sound familiar? If your team spends more time waiting for approvals than making decisions, it’s time to streamline. Cut the unnecessary layers and empower your people to act. When they can make decisions without navigating a maze, they move faster. It’s a win for everyone.

3. Create a culture of shared responsibility

The sabotage manual emphasizes that saboteurs work best when they feel part of a larger movement, that they are part of a bigger team working towards the same goal. They need to believe that others are fighting the same battle, that their efforts, no matter how small, are contributing to something larger.

“Since the effect of his own acts is limited, the saboteur may become discouraged unless he feels that he is a member of a large, though unseen, group of saboteurs operating against the enemy or the government of his own country and elsewhere. This can be conveyed indirectly: suggestions which he reads and hears can include observations that a particular technique has been successful in this or that district. Even if the technique is not applicable to his surroundings, another's success will encourage him to attempt similar acts. It also can be conveyed directly: statements' praising the effectiveness of simple sabotage can be contrived which will be published by white radio, freedom stations, and the subversive press. Estimates of the proportion of the population engaged in sabotage can be disseminated.”

As leaders, it’s our job to create that sense of shared responsibility. It’s not just about telling our team that their work matters—it’s about showing them how their work connects to the bigger picture.

In our last all-hands meeting at Dékuple, we shared the progress with a major customer. The feedback was overwhelmingly positive, and it boosted everyone’s morale.

4. Recognize and promote efficiency

The sabotage manual stresses inefficiency. Inefficiency is probably right after bureaucracy in the list of the most important sabotaging tools. Not only that: the manual recommends rewarding and promoting inefficient workers to cause chaos.

“To lower morale and with it, production, be pleasant to inefficient workers; give them undeserved promotions. Discriminate against efficient workers; complain unjustly about their work.”

“Work slowly. Think out ways to increase the number of movements necessary on your job: use a light hammer instead of a heavy one, try to make' a small wrench do when a big one is necessary, use little force where considerable force is needed, and so on.”

“Contrive as many interruptions to your work as you can: when changing the material on which you are working, as you would on a lather or punch, take needless time to do it. If you are cutting, shaping or doing other measured work, measure dimensions - twice as often as you need to. When you go to the lavatory, spend a longer time there than is necessary. Forget tools so that you will have to go back after them.”

“Do your work poorly and blame it on bad tools, machinery, or equipment. Complain that these things are preventing you from doing your job right.”

The real takeaway here: reward efficiency. Celebrate the people who get things done and do it well. Recognizing and rewarding the high performers in your organization isn’t just good for morale—it sets a standard that drives everyone to do better.

Whether it’s a shout-out in a meeting or a more formal reward system, it’s essential to make efficiency and effectiveness the norm, not the exception.

5. Build a Safe Space for Failure and Risk

Fear of getting caught makes saboteurs less effective.

“The amount of activity carried on by the saboteur will be governed not only by the number of opportunities he sees, but also by the amount of danger he feels. Bad news travels fast, and simple sabotage will be discouraged if too many simple saboteurs are arrested.”

In leadership terms, fear stifles creativity. If people are too afraid to make mistakes, they’ll stop taking risks altogether. You need to make it safe to fail. Create a culture where failure is part of the learning process, not something to be punished. When people know they won’t be “caught” for trying something new, innovation can truly thrive.

In Conclusion: Build, Don’t Sabotage

The “Simple Sabotage Field Manual” shows us exactly what *not* to do. But when we flip the advice, we get a clear guide for building strong teams and organizations.

Remember: Sabotage is easy. Leadership is about building something better.